Italian writer and publisher Francesco Verso is known in China as the “Marco Polo of science fiction”, because of the frequency of his travels there in order to arrange publications and strengthen relations. I’m not nearly in his league, but all the same this year I received no less than three invitations to literary events in China. High time to take a look at the country: what’s happening there?

A small disclaimer: my knowledge about these things is necessarily incomplete. As a non-Chinese I have to make do with the information I can find. I’ll also be weaving my personal experiences in China into this story—stay tuned for the Southern China Book Fair, Future Creation Workshop and more!

The Three-Body Problem

Fact is, science fiction is currently having a real moment in China. The world at large learned of this a little over ten years ago, when Cixin Liu’s epic SF novel “The Three-Body Problem” won the 2015 Hugo Awards, but the series had by that time already been a smash hit nationally. It had been published from 2006 on in the country’s oldest SF periodical, Science Fiction World (科幻世界 kēhuàn shìjiè, founded in Sichuan’s capital Chengdu in 1979), and promptly set fire to everyone’s imagination. After the trilogy’s worldwide breakthrough (an unofficial fourth entry was written by fan writer Baoshu, who used it to launch his own career and inadvertently ensured Liu would never write a “true” sequel of his own), things really got cooking. “3-Body” became a phenomenon that was fired up further with countless luxury publications, an attempted film adaptation, a thirty episode series produced by Tencent and after that an international version on Netflix.

It’s hard to describe how powerful such a dynamic in China can be when all the stars align and both the business world and government choose to back it. Suddenly, science fiction was considered an admirable expression for society at large: scientifically minded, forward-thinking, a way to enthuse young people to work in technology, engineering and research. Abroad, SF turned into a mode of “soft power”, a way to express that the future has a Chinese flavor. Visit Chengdu, Guangzhou or Chongqing and you can hardly deny it. “China’s already living in 2030” is a phrase I heard there.

Talent development

There are at the same time concerns about how long this SF trend will continue. Even at the Worldcon that was held there in 2023, I heard mutterings that the “science fiction industry” is primarily a “3-Body industry” focused almost entirely on Liu’s work. No argument there. For commercial parties, it’s hard to escape the sheer gravity of the name and the increased chances at success when using his work. Yet I also see many initiatives spring up—incubators and contests involving sometimes dizzying amounts of prize money—that are aimed at young talent and discovering new stories.

One of those places is the Fishing Fortress Science Fiction College in Hechuan, a small municipality next to “cyberpunk city” Chongqing. This futuristic offshoot of the College of Mobile Communication was founded in 2019 by language professor and SF enthusiast Fan Zhang and the aforementioned Francesco Verso. It’s housed in a building shaped like a UFO and its staff organizes at least two big events per year: its own SF award and the recently renamed Future Creation Workshop. This last one encompasses a week-long workshop where Chinese and international mentors provide lectures and guidance to a selection of talented young writers. A detailed report, by writers Lavie Tidhar and James Patrick Kelly, of the first workshop was published last year in American Locus Magazine. Kelly will be present as a mentor yet again in 2025, together with authors such as Baoshu, Naomi Kritzer and Roderick Leeuwenhart. What?! Yes, yours truly will be joining in October as well.

Next to the workshop sessions, all mentors are expected to hold one in-depth lecture for participants and one broader lecture for the faculty in general. For the first one I’ll discuss science fiction definitions and for the second non-human perspectives in the genre—two favorite subjects of mine, so preparing them was already fun. Since the students may not all speak fluent English, the workshop will employ a mix of translators and apps for instant subtitles, and if that should fail we’ll always have our hands and feet to communicate.

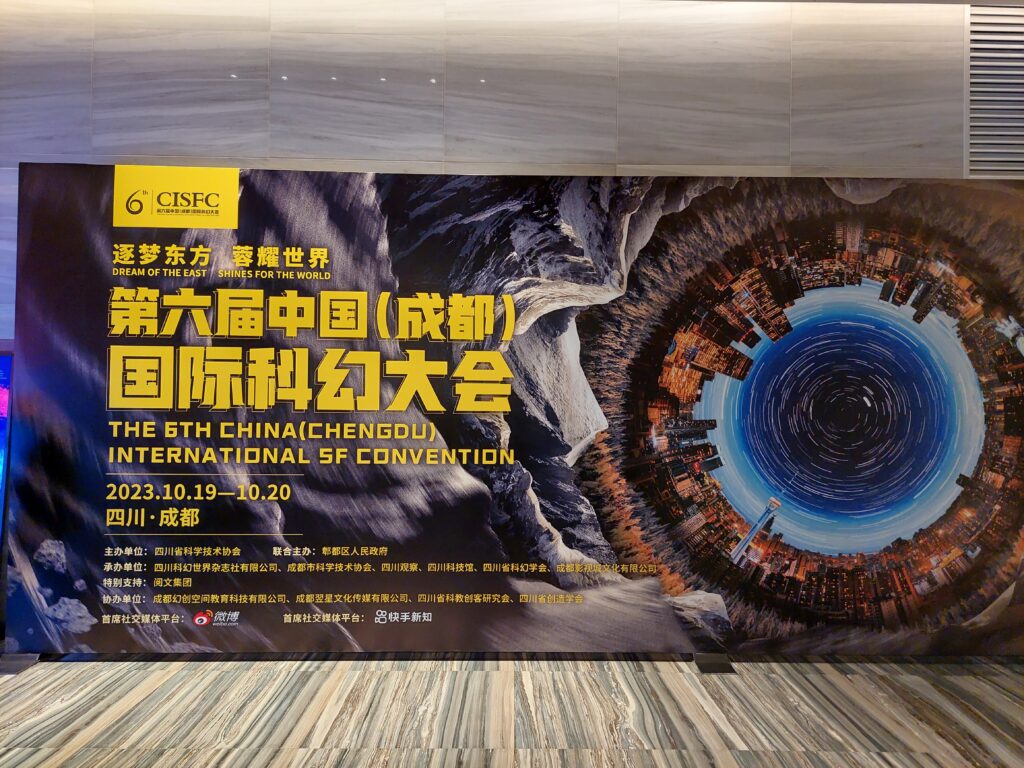

Galaxy Science Fiction Convention 2025

To further demonstrate the liveliness of SF in China: one month before that time, in September, the bi-annual, recently renamed Galaxy Science Fiction Convention will take place in Chengdu. A home game for Science Fiction World of course, who are partly responsible for the organization. Last time the event coincided with Worldcon and had a slightly more business-oriented theme to complement the fannish other program. Beyond the usual panels and parties, “Chengducon” is also the place where the annual Galaxy Awards are bestowed. I’ll be sitting in the theater with rattled nerves, as the Chinese edition of Star Body is shortlisted for the category “Best Introduced Book”, essentially best foreign or translated SF novel. In any case, I look forward to returning to Chengdu. Not only is it the prime spot for viewing pandas, it’s also a splendid city with at least one brilliant, vegan hotpot restaurant.

The Galaxy Science Fiction Convention is, by the way, only one of many yearly SF cons in China. Following the WeChat Moments of my writerly acquaintances and friends there, it sometimes seems as if there’s a huge event happening every week.

Tropical futurism

Something that wasn’t entirely science fictional, but did have great personal value to me, was the Southern China Book Fair held this August in Guangzhou—one of the huge cities that together make up the “Greater Bay Area”, the largest metropolitan region in the world. I was invited to be one of the international guests there and though, as you can read, I already had several things planned in China, this was too good an opportunity to pass up. And so I flew for a single week to the province of Guangdong, where summer means an average temperature of 35° Celsius and 80% humidity. Luckily, truly everything there is equipped with air conditioning, so the main annoyance whenever I stepped outside for at most thirty minutes was that my glasses promptly misted over.

The five day literary event itself had a strong international push, with an entire giant hall (one of four) occupied by pavilions dedicated to all manner of nations, regions and continents. My home base was of course the European one, which housed the Dutch, French, German and Polish sections. This year’s official guest country was Vietnam, so its pavilion was at least twice as big as the others and richly decorated, but all displayed their country’s local charm. Notably the Arab and Central Asia booths managed to effectively conjure up visions of nomad falconers and silk road civilization. These places were co-designed and staffed by the respective local consulates, so the first day felt like a diplomatic event with all the consuls opening their pavilions—and the media attention it garnered. As for the European countries, they all brought their own flavor. The Dutch aired non-stop episodes of famous cartoon rabbit Nijntje / Miffy, the Polish sold amber jewelry and wodka, and the German featured a jolly man from Munich who grilled sausages. It was trading on national stereotypes with a knowing wink.

As for my presence, the organizers of the fair’s international section—Beijing Gliese Culture & Media Co—spared no expense publicizing I was there and it was a strange feeling seeing my author photo blown up across dozens of banners, posters and displays across the Canton Fair Complex and Guangzhou subway. The thing that honored me most, however, was seeing Star Body on display next to The Three-Body Problem. Xiangxi Kong, an editor at SFW, had arranged for a big panel presentation with me and SF critic San Feng on the stage with a signing session afterwards. It was tremendous to have over a hundred fans listen to the talk and line up for over an hour to have their book (or sometimes multiple copies) autographed and pictures taken. I was also interviewed for various channels and local tv, so after those initial two days it was good to have a day of relaxation and touring the city, with an assistant from the organization as our guide. Guangzhou itself frequently seemed like science fiction. I got a ride in a voice-controlled car equipped with massage chairs, an entertainment system putting those of airlines to shame and seamless connectivity to external cameras on toll booths. We also visited the Canton Tower, a true piece of high tech architecture (designed by Dutch, no less).

This moment’s literature

Back to SF in China in general. That the genre, and in a broader sense the progressive values it stands for, is alive and kicking there is plain to see. It’s apparent from the science fiction museum built for Worldcon, pop up art galleries, street art, the way regular sectors employ SF aesthetics to drum up excitement, exhaustive roadmaps for the next steps for 3-Body. Backing all this are truly mindboggling investments from local governments and businesses that are all too keen to get in on it and hope to create jobs in tech and entertainment. If the official numbers are to be believed, the total revenue of the Chinese “SF industry” in 2024 was over 100 billion yuan, about 12 billion euros, the film industry (with blockbusters like The Wandering Earth 1 & 2) accounting for a non-negligible portion of that. Is this a bubble waiting to pop? Perhaps, but at least it’s one that suits this moment in China: the country has been modernizing at an incredible pace, currently generates more solar energy than any other and is developing its space program and infrastructure with advanced bullet trains between its megacities. Science fiction is the right cultural expression for these societal lunges forward.

Worldwide language

Ten years after Cixin Liu’s Hugo success, SF is still going strong in China. It has its sights set mostly on its own country’s output, of course, but doesn’t forget the rest of the world: both its classics and modern works. Dutch language writers have a modest place within this. Flemish writer Frank Roger, for instance, has by now had dozens of his stories translated into Chinese, a record that no one will soon surpass. The best-known Dutch writer will still be Robert van Gulik though, whose famous tales of Judge Dee from the 1960s made a big impression worldwide.

Science Fiction World prides itself on presenting SF from all corners of the world in their book series and “SFW Translation” magazine. So it seems that Francesco Verso’s efforts to spread his notion of “decolonizing the future” has found fertile ground in China. Enough reason for me to stand by my careful assessment: China is currently one of the most interesting countries to be published as a science fiction writer. 九天揽月 jiǔ tiān lǎn yuè, find the highest spot and pick the moon!

This report takes me back, thank you so much! when I lived in China I visited and reported on the Galaxy Award many times and was even nominated twice myself. :’) When I moved to the west I was surprise how little recognition they have. My publisher had never heard of it! Hopefully that will change but nominating process does need to be more transparent and less SFW dominanted. How was the ceremony this time?

Hi Zihan, thank you for writing such a nice response! The ceremony was amazing, in no small part because my book actually won the Galaxy Award! The new report is online now:

https://www.roderickleeuwenhart.nl/star-body-wins-a-galaxy-award-a-galaxycon-2025-report/

I hope the awards will get a little more recognition in Western SF fandom too.